summary:

Wall Street Just Doesn't Get It: Meta Isn't Losing Money, It's Building a New WorldYou ca...

summary:

Wall Street Just Doesn't Get It: Meta Isn't Losing Money, It's Building a New WorldYou ca... Wall Street Just Doesn't Get It: Meta Isn't Losing Money, It's Building a New World

You can almost picture the scene on Thursday morning. A trader, coffee in hand, glances at Meta's Q3 numbers. Record revenue—over $50 billion for the first time. Earnings per share crushing expectations. A company that, by every traditional metric, is firing on all cylinders. He probably allows himself a brief, satisfied smile. And then, the earnings call transcript loads. The capital expenditure forecast hits the screen—$72 billion this year, maybe more next year—and that smile evaporates. The coffee goes cold. All he sees is red.

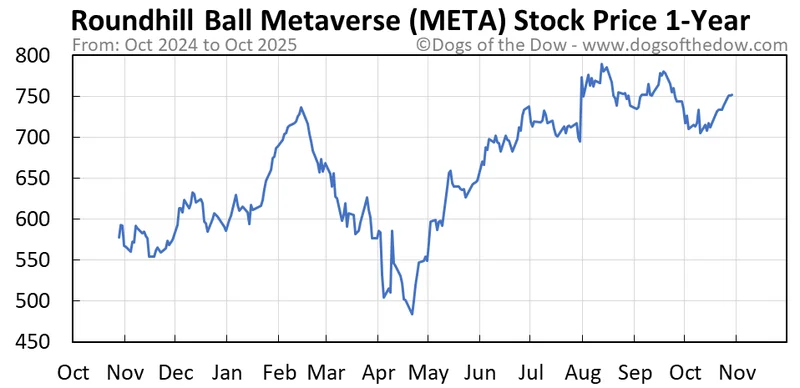

Within minutes, the `meta stock price today` was in a freefall, tumbling over 13%. The headlines wrote themselves: "Meta Plummets," "Investors Spooked by Spending." And as I watched this unfold, I honestly just sat back in my chair, speechless. Not because of the spending, but because of the market’s breathtaking failure of imagination. This isn't a story about a company losing money. This is the story of a company building a new reality, and Wall Street is complaining about the price of the bricks.

What we are witnessing is a fundamental disconnect between two different languages: the language of the quarterly report and the language of generational change. The market is asking, "What did you earn for me in the last 90 days?" Mark Zuckerberg is asking, "What will humanity be doing for the next 90 years?" The panic over a $70 billion "loss" in Reality Labs since 2020 is proof that we've forgotten what it looks like to build something truly new.

Is $70 billion a lot of money? Of course. But let's reframe it. The United States spent an inflation-adjusted $280 billion to put a man on the moon. Was the Apollo program "unprofitable" in 1965? The interstate highway system cost over $500 billion in today's money. Was it a bad investment because it didn't turn a profit in its first few years? These weren't expenses; they were foundational investments in the future. They built the infrastructure upon which new economies, new industries, and new ways of life could flourish. That is precisely what Meta is doing.

The Cost of a New Continent

When you read that Meta is spending billions on "AI superintelligence," it sounds like something out of science fiction. In simpler terms, it's about building the cognitive engine for the next computing platform. It’s the foundational intelligence that will allow your AI glasses to do more than just show you notifications; it will allow them to understand your context, see what you see, and provide helpful information about the world around you, seamlessly. This is the kind of breakthrough that reminds me why I got into this field in the first place.

The money isn't just vanishing into some "metaverse" void. It's being poured into concrete and silicon: data centers, custom chips, and the immense computational power needed to train these new forms of intelligence. This is the digital equivalent of laying railroad tracks across a continent. It's a brutal, expensive, and deeply unglamorous process, but without those tracks, nothing can move.

Skeptics like Ryan Lee at Direxion worry that the "cash cow of the company, advertising, no longer remains the top priority." To which I say: thank goodness. A company that is only focused on milking its current cash cow is a company that is blissfully unaware of the approaching disruption. Look at the history of technology. Look at Kodak, Blockbuster, Nokia. They were all fantastically profitable, right up until the moment they weren't. True vision isn't about optimizing the present; it's about having the courage to sacrifice a piece of it to build the future. What is the "right" price to pay for the next dominant computing platform? Is it more or less than the market caps of today's smartphone giants?

This is where the scale of Meta's ambition becomes so clear, especially when you compare it to the competition. While `microsoft stock` and `google stock price` are also soaring on the back of AI investments, Meta's play is different. It’s not just building the AI brain; it’s building the body, too, in the form of headsets and, more importantly, those sold-out Ray-Ban glasses. The vision here is a vertically integrated future where the hardware and the AI are designed in perfect harmony, creating an experience so intuitive and powerful that the idea of pulling a phone out of your pocket will one day feel archaic—it's a staggering thought, this idea that the gap between our digital and physical lives is closing so fast that the very interface we use to access information is about to dissolve into our line of sight.

Of course, with this power comes immense responsibility. We must ask ourselves: as we build these new worlds, who is writing the laws of their physics? Who ensures they are equitable, safe, and empowering? These are not trivial questions, and they must be part of the engineering process from day one.

The Foundation Is the Product

Ultimately, the market is making a classic category error. It’s judging Meta as if it’s selling a product, like a phone or a car. It analyzes the sales of the Quest 3 and the losses in Reality Labs and comes to a simple, flawed conclusion.

But the product isn't the headset. The product isn't even the glasses. The product is the foundation.

The tens of billions in capital expenditure aren't a cost center; they are the price of the real estate upon which the next generation of social connection, entertainment, and work will be built. Investors are worried that Meta needs to find "a bevy of new revenue streams," but they're missing the point. If Meta successfully builds this platform, it won't need to find new revenue streams; it will be the stream.

What we saw on Thursday wasn't a sign of a company in trouble. It was a sign of a market that has become so addicted to the sugar rush of quarterly gains that it can no longer stomach the protein of long-term, world-changing investment. Let them sell. Let them panic. History shows that the greatest returns don't go to those who flee from the cost of construction; they go to those who had the vision to see the cathedral when all anyone else could see was a pile of stones.